A practical variable-rate pricing scheme

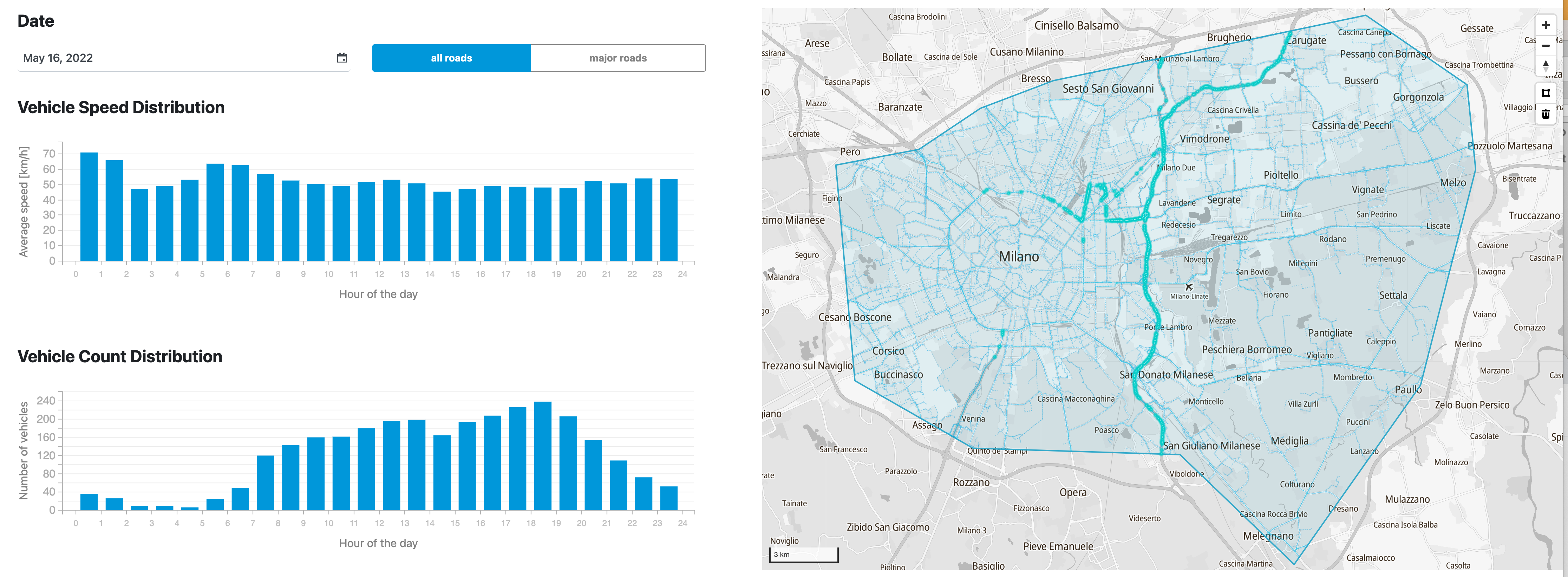

A simple yet effective variable-rate pricing scheme can be created by setting just a few different prices for all roads in the congestion zone, reflecting overall traffic patterns throughout the day. For example, the lowest price for driving during the night, the highest price during morning and afternoon rush hours, and something in between for day drives between rush hours. Lower prices may also be set for less busy weekend days or holidays.

While it may not be immediately apparent, the variable-rate road price must be expressed in terms of cost per kilometer or cost per minute of use. That way, the total cost of a trip through the congestion zone would be proportional to the vehicle's real contribution to congestion. Note that the existing congestion charging schemes in London, Milano, Rome, Stockholm, and other cities without exception charge driver an equal lump sum for entering the congestion zone regardless if she/he drove only 100 meters or 100 kilometers within the zone.